Early in 2013, Moore Museum was contacted by Judy Keeler who was researching the Reilley family property in Mooretown. Judy is the great-great granddaughter of Charles Reilley, the owner of the Reilley cottage, which forms part of Moore Museum’s heritage village.

Judy graciously offered to interview her mother about her memories of Mooretown and the Reilley house and cottage. The following is an introduction by Judy Keeler and then the memories she recorded of her mother’s times spent in Mooretown.

Introduction

By Judy Keeler

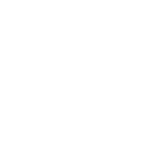

All my life I have heard my mother tell me about ‘Mooretown’, and ‘the big house’ where she spent every summer from the time she was a toddler until her early teens. The magnificent house along with the cottage, barn and several hundred acres belonged to Aunt Hootie and Aunt Phyllis Reilley, who were half-sisters, the daughters of Charles Reilley. They lived in the house almost seventy years. When they could no longer manage the house with six bedrooms, a kitchen, summer kitchen, drawing room, library, dining room and servants’ quarters, they moved into the Reilley cottage.

My mother always believed her great grandfather Charles Reilley had built the house where her Aunt Hootie and Aunt Phyllis lived. Imagine my astonishment to discover the house had been built in 1855 by Raymond Baby, one of James Baby’s five sons. Charles Reilley purchased the property from Raymond Baby in 1875.

My mother grew up in The Beach in the east end of Toronto. My father grew up on the banks of the Humber River in the west end of the city. He grew up in the area known as ‘Baby Point’. James Baby had purchased 114 acres along the Humber River, one of the most strategic areas in the province, and named it ‘Baby Point.’

Today ‘Baby Point’ is a residential enclave, is threatened by determined developers. Concerned residents have stepped up to address heritage, development and nature conservation by forming “The Baby Point Heritage Foundation”. Prompted by my interest in local history, the connection with my father, and the fact that almost every neighborhood in Toronto is on the endangered list, I attended one of their meetings.

The Baby-Reilley house in Moore Township was built in 1855. At age 41, Charles Reilley purchased the house, barn and surrounding property consisting of several hundred acres. By 1893 Charles Reilley had built a cottage for his brother and sister who never married. That cottage remains today as part of the Moore Museum. When the Township acquired the property in 1962, ‘the big house’ was demolished. The cottage is all that remains as part of the original property.

My mother’s grandfather Francis Reilley, was born in ‘the big house’ in Mooretown as were several of his siblings, some of whom my grandmother never met since they had died before she was born. My grandmother, Frances Reilley was born in 1898.

At the peak of the oil boom at the height of the Victoria era, Charles Reilley had a hotel and liquor store on the main street of Petrolia. He had a hotel in Corunna, and one in Courtright according to my mother. Charles Reilley must have been an enterprising man and one of some means since he owned the wharf in Mooretown and neither of the two half-sisters who lived in ‘the big house’ ever worked. Aunt Hootie who handled the business collected revenue from pastures she rented to farmers.

It appears that an older brother Philip Reilley must have been first to settle along the St. Clair River in Moore Township. His name appears in early records. He died in 1874.

My mother’s fondest childhood memories are of ‘the big house’ in Mooretown. It is where she acquired her love of antiques. It is one of the great follies of our country that we ignore and destroy our history.

When Jacques (James) Baby was awarded a prominent position in the government of Upper Canada for taking a stance against the Americans during the War of 1812 he acquired land. Every ambitious young immigrant acquired as much land as they could afford, since in the old country you could never own land. You rented it from landed gentry.

James Baby, through enterprise, promotion and privilege would eventually acquire 80,000 acres in Ontario. One of them was Lot 38 in Mooretown, the land the Reilley family would call home for the next century.

James Baby, who is known as ‘The Forgotten Loyalist’, also purchased a sizeable piece of real estate along the Humber River in 1819 that was a pivotal trade route for the Indians and well established as a French Canadian fur trading post called Fort Rouille.

The natives called the area the ‘The Carrying Place’. It is described by many a pioneer who penned their travels. This location on the Humber River was used for portage and was an important destination for the early settlers and lively subject for diarists such as Anna Jameson and Mrs. Simcoe.

Baby’s good friend Thomas Fisher built the first gristmill on the banks of the Humber River, close to what is now Bloor St. W. That mill eventually became part of “The Old Mill” restaurant designed and built by Home Smith in 1911. Home Smith developed The Kingsway. The homes he designed were English Tudor, built from the flat stones of the Humber River.

These prestigious homes line winding streets and cost a fortune today. Contemporary renovation guts most Home Smith residences today. The real estate agent may be selling ‘heritage’ but little of it remains. Today the exterior is all that will be left of original home. A “Great Room” with wall size plasma TV above a gas fireplace will replace the living and dining room. Bathrooms are the size of yesterday’s bedrooms, and the house is so wired you can turn everything on from a smart phone before you get home.

Thomas Fisher would eventually move from the Humber to Moore Township and hold a prominent position in the community. His friends on the banks of the St. Clair River included James Baby and Archdeacon Strachan (later Bishop Strachan). Thomas Fisher became Reeve of Moore Township in 1845, not many years before he died.

The Thomas Fisher Rare Library on the University of Toronto campus is not only one of the most important archival institutions in the country, it was created to house the Fisher’s extensive book collection (including the collected works of Shakespeare and extremely rare Bibles). Fisher Rare Books is connected with the mighty Robart’s Library, it also, through history, connected to our family.

My father’s medical fraternity stood on the site of the Fisher Rare Library. My father recalled Sir Frederick Banting (Nobel Prize Winner and discoverer of insulin) dropping into the old frat house. I live in the same apartment in the same house on Washington Avenue where Bill Banting (the only son of Sir Frederick) lived. I attended Bishop Strachan School and Trinity College in Toronto both founded by John Strachan.

My mother, on one of her antique expeditions acquired John Strachan’s Sheffield Plate roast cover, his initials engraved in sterling silver.

It is likely that Raymond Baby inherited the house in Mooretown on the land James Baby purchased. His grandfather’s main residence was in Windsor (previously known as Sandwich). Apparently James Baby was both friend and ally to General Isaac Brock and rumors have it that Brock set up post in the Baby residence in Sandwich. It is not difficult to discern these two gentlemen had like minds, a privileged upbringing and shared similar pursuits.

It appears as though Lot 38 in Mooretown may have been intended as a summer place for the Baby family. It is possible some of the most important residents of the province may have visited ‘the big house’ in Mooretown.

James Baby’s holdings were so extensive he named several landmarks along a long stretch of St. Clair River ‘Baby’s Point’. It is likely a prestigious architect from Sarnia or Sandwich was hired to construct the home my mother would come to cherish. The Baby Creek ran through the property. Members of the Baby family occupied the house from 1855 until 1875.

The house was classic Victorian Gothic, grand by any standard. Half-sisters Hortense and Phyllis Reilley lived in ‘the big house’ then moved to the cottage in their later years. They owned and maintained the entire property for seventy years.

It is tragic this great piece of history and architecture met its demise. ‘The big house’ in Mooretown was a work of art and would have made a wonderful museum. Built by one of the most prominent and wealthy families in Upper Canada, the Baby-Reilley home might have been preserved and become a tourist destination to showcase an important past and find value as a historic home. The detail and craftsmanship that went into the house could neither be afforded nor duplicated today.

Our heritage, once gone, is never revived. Yet when we appreciate and conserve it, our past tells us a tremendous amount about how people lived and what that has to teach us today.

The favorite time of my mother’s childhood was in effect the last gasp of the Victoria era. It was a time when manners were a code of civility and there was cohesiveness in society lost today.

When a Britain’s Bernardo Home Child arrived at the doorstep of Aunt Hortense and Aunt Phyllis, they took him in. Andrew Halliday lived in the servants’ quarters. He was the handy man and gardener. Andrew looked after the chickens, tended two Irish wolfhounds and delighted when members of the family came for a summer visit. The Reilley sisters took care of Andrew Halliday after he could no longer work, and buried him when he died.

For years, my mother’s family visited from Toronto, and the rest of the family came to visit from Chicago. By all accounts, summer was a busy and enjoyable time.

It is a tribute to local interest and volunteers, the arduous work of any museum that local history remains intact for future generations. When it does, it speaks volumes about how things are connected, it tells about the way we were and what we’ve lost.

Unfortunately my father died in 2006 so he did not live to share in this coincidence of my mother’s connection to the house in Mooretown and ‘Baby Point’ where he was raised. My father would be delighted and call this “synchronicity”.

James Baby had purchased the land along the Humber River in 1819 and called it ‘Baby Point’. The Indians referred to the banks of the Humber River as the “Garden of Eden”, so plentiful were fish, flora and fauna. Seneca burial grounds dating back to 1600 have been excavated along its banks. Flint arrowheads from the bottom of the Humber now reside in the Royal Ontario Museum.

Etienne Brule and Samuel de Champlain visited there. The land itself forms a point, making it particularly advantageous from a military point of view. This leverage was not lost on the government that expropriated the land from Raymond Baby in 1910. The government of the day maintained they needed the point as a militia post anticipating WWI. They immediately turned Baby Point over to Home Smith who went on to develop the Kingsway and built “The Old Mill”.

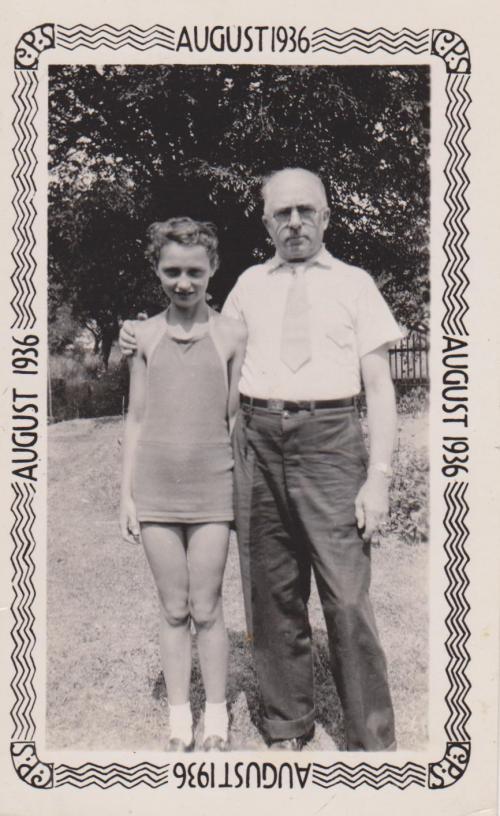

My mother is the last living member of her family who remembers the house in Mooretown. Here are my mother’s memories in her own words.

February 2013

Mary Keeler’s Memories of Mooretown

I remember first going to Mooretown when I was about three or four years of age. We always stayed in the big house. There was my Mom and Dad, then came the twins Jack and Tom, my sister Anne, and my brother Lawrence. We had the Plymouth my Dad bought in Long Island in the mid-1920’s and we drove in it to Mooretown every summer.

When we went to Mooretown as a young child usually my Mom and Dad would come up then stay a few days. When I got older, they would drop me off and I would stay for a couple of weeks. My parents would come up and get me or, Aunt Hootie and Aunt Phyllis would take me to the train station in Sarnia. I would go by train to Toronto and my Mom and Dad would meet me at Union Station.

The Big House

I remember the house was magnificent. That is where I first grew to love antiques. It is where I first remember seeing marble fireplaces. That is also where I got my love of antique Christmas decorations. There was a box in the drawing room with Christmas tree ornaments in it and I can remember there were also great big bunches of grapes and they were silver. The decorations were in a box up on a shelf. The Jarvis kids and me found the box and brought it down.

In front of the big house there was a great big circular driveway lined with hickory trees and a row of hitching posts. The big house was always beautifully maintained by Aunt Phyllis and Aunt Hootie.

Inside the front entrance was a foyer with a tall table, with a top the size of a large dinner plate. My great grandmother’s calling card tray was kept on that table. Anyone who came to visit left a calling card.

While the house was not on the river you could see the river from the house. My great grandfather owned all the land down to the river. (Some of it got sold to Charles Yates, but he never did anything with it as far as I know.)

To the right after the foyer was a sitting room with a marble fireplace and a large pocket doorway that led into a large bedroom. To the left was the drawing room with Victorian furniture and a marble fireplace. There was carpeting throughout.

They had Victorian armchairs with matching footstools. Each footstool had beaded needlepoint. There was a grand piano in the corner covered with gold velvet chenille and fringe. Behind the drawing room was the library. The dining room ran the width of the house along the back. Then you went down a hallway that went into a massive sized kitchen. That was where my aunts ate most of the time since it had a large table. Beyond that there was a summer kitchen. Then there were some anterooms that served as the pantry.

There was a root cellar where they kept vegetables from their beautiful garden. The door went into the basement, or root cellar on one side of the house. There were two wells at the big house, one either side of the kitchen. In the summer Aunt Phyllis would put her milk, butter and perishables into a white granite pail that she lowered into the well. There was a long veranda along the side that overlooked the chicken coop. In the summer they kept fruit and vegetables in the ‘cold cellar’ you got to from the side door.

There was the most beautiful balustrade going up to the second floor. Upstairs in the big house there were six bedrooms, three on each side. Each bedroom had an iron or brass bed, and a chamber pot underneath each one of them. Every room had a beautiful washstand. At the end of the hall you went down a few steps and there were several smaller bedrooms along the back of the house for servants.

The big house was lit by coal oil. My aunts cleaned the lanterns every morning. They did have gaslight outlets, but the gas was never hooked up.

Past the six bedrooms, you went down three steps, and there was the most magnificent bathroom. The bathtub was copper, the basin was copper with a pink marble surround, a very fancy place to put soap and a glass. The toilet had the water boxes up attached to the ceiling, with a long chain and a handle that you pull. The house was never hooked up to have running water. As a result the bathroom was never used.

There were four or six smaller rooms there for the help. That is where Andrew Halliday lived. Andrew must have been about fourteen when he arrived in Canada as one of the Bernardo orphans sent to Canada to work on farms. He spent his whole life in the big house (my aunts took care of him when he got old. When he died, my aunts buried him).

Andrew Halliday took care of the gardening and the chickens. Other than that, Andrew kept to himself. He read his Bible every night.

My aunts may have had a couple of cows too, but Andrew did not do any farming. I was told that the house originally had close to six hundred acres that my aunts rented out to farmers.

During the summers when I was young, I had friends nearby who lived in Detroit and their family built a little cottage across the street (that street was a gravel country road). The Jarvis family had one son and three girls, and they were my friends. We used to have picnics and go swimming together off the dock where I learned to swim. That dock and the wharf belonged to my great grandfather Reilley, and he also had an icehouse there beside the wharf. It was painted red, and the ice was stored in sawdust. The ice was cut from the river.

When I played with the Jarvis kids we either played in the orchard, climbed apple trees, or picked hickory nuts. There were about ten trees on the circular driveway. It was lined with hickory trees. We collected them and Aunt Phyllis would use a lot of them to make Christmas cake.

There were also the Alvistons and they had several adult sons who worked on the boats. I used to like to go over and visit Mrs. Alviston because she always gave me a home baked cookie. They were good friends of both my aunts.

When Andrew looked after the chicken coop, my aunts had about a hundred chickens. He used to take me out (and my brothers and sisters if they were there) when he was collecting eggs. We were always warned not to take out the ‘false’ egg. Each one of the nests had a false egg.

There was a stile that went into the orchard, between the main driveway and the cottage, and Andrew would help us over the stile. In the orchard itself there were apple trees. On the other side of the big house there were some pear trees and a beautiful vegetable garden that Andrew Halliday and Aunt Phyllis planted and looked after.

I remember the picturesque creek that went through the property. My aunts called it Bear Creek. One time Aunt Phyllis allowed me to go to the back of the creek to have a wiener roast with the Jarvis kids, and she provided the pots, the wieners and the rolls and everything she got at the General Store run by Mr. Hillyer. (The General Store always had a barrel of apples outside the door for the taking. Everyone was welcome to help themselves to an apple. There was a bench outside on the porch and you’d always see two or three farmers smoking.)

We were warned not to go where any of the cows were. Anyway the cows wandered over to where we were and that was the end of our wiener roast! The cows trampled all the pots and pans and we ran back to the house. Aunt Phyllis wasn’t too happy about it, but I think she realized it wasn’t really our fault because the cows came. We weren’t all that old and we were scared of them. I think I was ten or eleven years of age.

There was a Blacksmith’s shop down at the corner and Aunt Phyllis used to take me down there just so I could see how they were shoeing horses.

Aunt Hootie didn’t bother too much about church but Aunt Phyllis was the one who went to the Catholic Church in Courtright approximately two miles away. Aunt Hootie would drive her and pick her up. I was only at church once in Courtright. The church in Corunna was six miles away.

Aunt Hootie drove in this old Model T Ford and she wasn’t a very good driver. The roads were gravel. To drive Sunday to Wallaceburg to the McCarron’s for Sunday dinner was quite the drive! I think the furthest she drove other than Wallaceburg was Sarnia.

Aunt Phyllis belonged to a quilting group and she made the most beautiful quilts.

My aunts went visiting and had many visitors who came by. There were garden parties on the front lawn and there were fairs. My mother won a lamb in a contest at the fair. There is a picture of her when she was in her teens in front of the big house, sitting on the lawn with the lamb in the picture.

Once my aunts moved into the cottage from the big house everything in the house was put out on the lawn for auction. I must have been a teenager. Once I became a teenager I didn’t go to Mooretown as often as I had since I had a summer job working at Simpson’s in downtown Toronto.

Every winter Aunt Hootie and Aunt Phyllis went to stay with the Yates in Chicago, but they were born and lived in the big house together for almost seventy years.

Their father, Charles Reilley, had built or owned hotels in Courtright and Petrolia. I can remember our dear friend Blondina Hoban from Petrolia (who grew up with my mother and most likely went to the big house when she was young) telling us the story of when she was a little girl seeing Aunt Hootie and Aunt Phyllis arriving in their carriage to visit their father at his hotel on Petrolia Street. They were beautifully dressed and carried long handled silk parasols.

That building is still on the main street but the brick is covered with some other material. Francis Reilley, the son of Charles was born in the big house most likely. When he married my grandmother they lived in Petrolia and that is where my mother was born.

Francis Reilley died when my mother was very young. She was somewhere around two years of age. Francis died as a result of pneumonia during a flu epidemic. He was on a train going out west for some kind of cure when he died. My grandmother and my mother got word while they were visiting family in Chicago.

My mother’s father, Francis Reilley, was in the liquor business in Petrolia with a gentleman by the name of Calnan. Their store was on Petrolia Street, down near the Kerr family home. The last time I was in Petrolia in the mid 1990’s, the store still had the name on it over the door. Whether that store survived the bad fire they had on Petrolia St. I don’t know.

The Reilley Cottage

The cottage that my great grandfather built on the property was built for a brother and sister who never married. They must have died before I was born because the cottage was empty as long as I can remember. Aunt Hootie and Aunt Phyllis eventually moved into it from the big house. That must have been in the early 1940’s.

There was one well beside the cottage. The cottage was quaint and really quite lovely. From the outside it had the veranda all the way around which had pillars with gingerbread on it. On the top of the roof at the cottage, was a wrought iron fence about four or five feet square. It was really fancy wrought iron fastened to the roof. The roof was a peak roof.

The lovely living room of the cottage went right across the front facing the river. To the left was a small bedroom which was Aunt Hootie’s bedroom and there was lovely entrance hall that had a very ornate clothes rack. There was a bench you could sit on and you put your gloves and mitts inside the box. It was six or seven feet long. It was quite large entrance hall. After you hung up your hat and coat the room you got into was the dining room. The dining room was beautifully furnished with a magnificent sideboard and a gorgeous chandelier that Aunt Phyllis used to have to go to Marine City to get the wicks.

In the dining room there was the telephone on the wall, and every time it rang, anybody who wanted to listen in, could. It was a party line. Aunt Phyllis had her favorite rocking chair there. She used to sit and always read The Detroit News.

After the dining room you were walking into the kitchen and on the right was a doorway into Aunt Phyllis’ bedroom. She had a brass bed with a high headboard and a dresser and a chair. The south-facing window overlooked the garden.

You walked one step down into the kitchen. Aunt Phyllis did all the housekeeping. Aunt Hootie couldn’t boil water without burning it. She looked after the business affairs.

There was the most beautiful wood burning stove that had a big water tank on one end to heat hot water. It had a lot of chrome Aunt Phyllis used to polish every morning with some kind of black polish that was kept in a tobacco tin. She used newspaper.

Aunt Hootie and Aunt Phyllis always kept the cottage in beautiful condition. Aunt Phyllis was a real homemaker. Aunt Phyllis did all of the domestic chores around the house. Aunt Hootie used to do a lot of gardening outside, and she really did have a lovely garden around the base of the cottage. There was a fence and she had lilac trees there. The last time I was there (1955), there was a line of evergreen trees.

My aunts knew an elderly gentleman named John Cashan who used to come and have a cup of tea with them about once a week at the cottage.

He’d come and say, “Mary, would you like a buggy ride?” and he’d take me for little ride along the River Rd. That was a real thrill for me because I had never been in a horse and buggy.

He’d pick up Aunt Phyllis and me in his buggy and we’d go to visit Hattie Taylor, Captain Taylor’s wife. Captain Taylor was the captain of a riverboat. I think at one time he had been the captain on the Tashmoo. Every time it went up and down the St. Clair River, he would toot the horn at his wife in front of their house.

At the time the Noronic burned in Toronto Captain Taylor was captain of that boat. He was invited to have dinner with friends who lived in Forest Hill Village. They were originally from Sarnia. The man of the house was an executive with Imperial Oil. Captain Taylor had been invited to their home. He was not taking time off when he should have been on duty. It was his time off.

Unfortunately he was blamed for the dreadful fire and he lost his Captain’s license, and ended up serving beer in a hotel in Sarnia. He was a close friend of my cousin Ken Yates from Chicago. Ken used to go up to Sarnia to visit Captain Taylor once he had lost his license.

It was terrible. A lot of the people on the boat were from Cleveland and many of them could not be identified. The fire started in a linen closet. A lot of the people could not be identified and are buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto.

Hattie Taylor was a very close friend of Aunt Phyllis and she used to come and visit the house. Mrs. Taylor would invite Aunt Phyllis for a visit.

The connection of my family to the Yates family is Aunt Jo was a daughter of Charles Reilley, the youngest one of the family. Aunt Hootie was a child from his first marriage. Aunt Phyllis was from the second so Aunt Hootie and Aunt Phyllis were half-sisters.

Aunt Jo was married to Herman Yates, who was Ken Yates father. Herman Yates was a druggist and he also had a son by the name of Herman who became a druggist. They also had a son by the name of Charles who moved to Wisconsin. Charles was a chemical engineer. I don’t think he ever married. Ken Yates is the son of Uncle Herman and Aunt Jo. The big house was left to the Yates.

I believe the furniture was auctioned off before the house was sold. We were all just sick about it. We didn’t know anything about it and the only thing Evelyn McCarron got was a round table she bought at the auction.

What I heard was the house was sold to an order of priests from Detroit to use as a summer home, but they only had it for about three years. Then an elderly priest bought it. Father Hallett moved in with his housekeeper, who was his sister, and they lived in the house year round.

All the windows in the big house had shutters and the shutters were all pretty well closed when Ken and Pat and 14

their two children came over for the summer (they stayed the whole summer in the cottage). Ken Yates would phone every day to check on Father Hallett. He used to see if his sister needed any groceries.

I don’t know what Ken Yates did with Aunt Hootie’s old car that had a rumble seat in the back and sat three in the front. I don’t know what Ken did with it.

Many years later, after the last time I saw the cottage, and the big house was boarded up, I was visiting my cousin Ed McCarron in Wallaceburg (his mother Alice, was mother’s Dad’s sister, a daughter of Charles Reilley, and she became Mrs. McCarron).

Ed wanted to show me his new little workshop in the garage at the back. Inside there was a workbench and underneath it a box of things wrapped in newspaper. I saw something sticking out.

“Ed, what is it?”

He said, “That was your great grandmother’s calling card tray.”

The tray was broken in four places, so really you could not tell exactly what it had been, but I took it to Birk’s in Toronto and had it fixed. That is the only memento I have of the house.

Mary Elizabeth Keeler

-30-